It is no secret that redevelopment of the Scarboro Beach Amusement Park property was a major turning point in the Beaches’ history. In the fall of 1925 the park’s owner, the local street railway company, closed the park for good and sold its entire site to Provident Investments, a property developer already active north of Queen Street. And Provident promptly demolished and cleared away all the park’s facilities, subdivided the property into building lots, and began selling the lots to builders who, over the next two years, blanketed the entire site – the last major tract of unbuilt land in the neighbourhood – with the sort of dense residential fabric already in place either side of it.

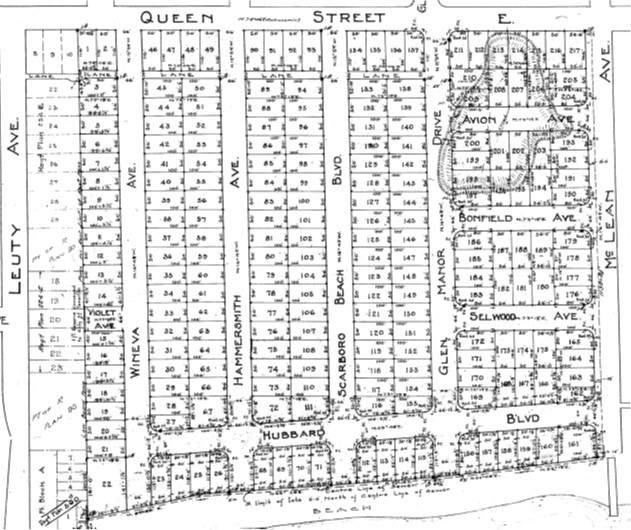

Provident Investments’ plan for the amusement park site, creating 217 building lots; the swamplands depicted in the northeastern section would bedevil construction there for years.

The most distinctive, and probably most commented upon, buildings in this new development were the fourplexes – originally called “double-duplexes” – built by the established local builder Price Brothers on lots it purchased from Provident. These novel structures, conceived and designed by the firm’s building superintendent, Harry Stevens, consisted of four single-floor, multi-bedroom flats, two up and two down, running front to back, each with its own small front porch. Price Brothers put up dozens of these, some with Spanish colonial details, along Glen Manor, Hammersmith, and Scarborough Beach, and a few on Queen Street as well.

The Price brothers Leslie (right) and E. Stanley stand either side of their father Joseph, founder and President of the firm, with their distinctive “fourplexes” under construction behind them.

But another important, if less widely recognized, feature of the redevelopment was the apartment buildings that went up around the site’s perimeter – several on Queen Street, the northern limit of the property, and some along the southern boundary too, on Hubbard Boulevard. They seem to have been generally accepted. In fact apartment buildings and rental flats became an essential part of the neighbourhood in these years, something contemporary opponents of multi-unit buildings often do not realize.

On Hubbard the first to be built was the Ramona, with ten units, completed and occupied in 1928; then came the adjacent Somersby with twelve units (now substantially rebuilt, fronting on Glen Manor). Hubbard Court Apartments, backing on Hubbard and facing the beach (See Sight #5), was started in 1929 though its fifteen units took several years to be completed and occupied. Hubbard Park Apartments, the largest, with twenty-nine units, was built in 1929 and fully occupied by the end of that year. All these buildings still stand, a testament to the range of housing types in the early Beaches neighbourhood.

The largest and by far the most conspicuous, Hubbard Park Apartments (42 Hubbard), is now public housing, something that many find surprising considering its elegant entrance and prime location. It has been in public hands for only about half its life. Like everything else in the neighbourhood, it was built as a private venture, and it remained privately owned until purchased by the City in 1975. What is especially interesting about Hubbard Park Apartments is not that it is unique, or old – it is the same age as the buildings around it – but how the stages of its long life so clearly reflect those of the neighbourhood overall.

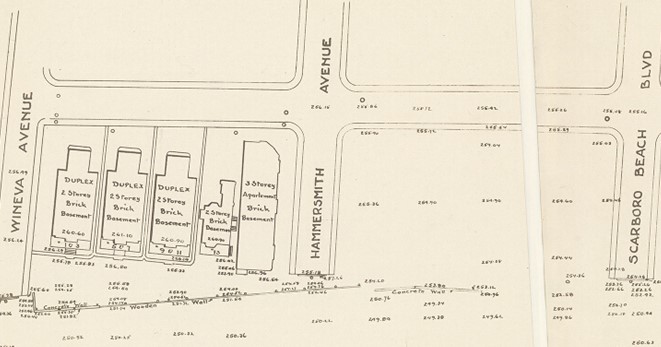

An apartment building was first envisioned for this site in 1928, by Price Brothers. They had owned land further east on the north side of Hubbard since 1927, and on it had built several fourplexes, but this stretch between Hammersmith and Scarborough Beach they had not acquired – it remained in the hands of the developer, Provident Investments. In September 1927, however, the City expropriated the south side of Hubbard for park purposes (see Sight #5), and in doing so transformed the north side into a strip of property fronting on a park and the lake. This, of course, considerably enhanced its appeal, and no doubt because of this Price Brothers arranged to purchase it in the summer of 1928.

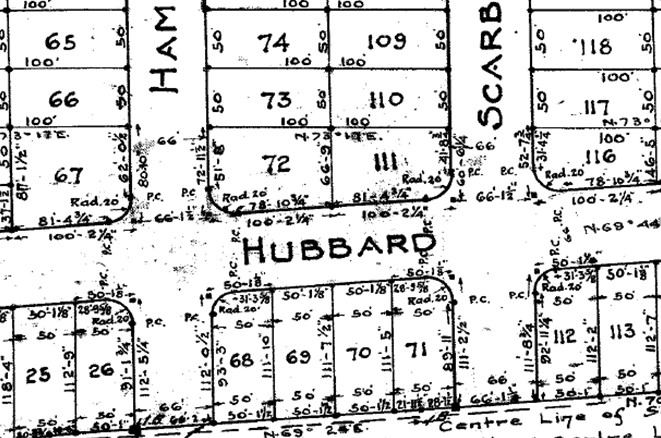

Price Brothers arranged to purchase the southern portion of Lots 72 and 111 in 1928, by which time the City had expropriated lots 68-71 (and lots further east) for parkland.

Such a special site called for a special plan, and Price Brothers concocted a humdinger. They would build a luxury apartment building here – a large, complex structure with 86 suites, and “all the perquisites of high-class apartments”: a roof garden, a swimming tank, private heated automobile garages, floors of “the finest hardwood,” and walls of “the best plaster and lath available.” Waterfront suites like these, they declared, “would bring four figures a month in some of the apartment houses in the bigger centres in the States.”

It was not to be. The reporter who related all this in July 1928 noted that the building had not yet gone beyond “the architectural plan stage,” and one suspects it had not even reached that stage, let alone gone beyond it. For reasons we will likely never know but probably have something to do with Price Brothers’ financial circumstances, and maybe their common sense, they abandoned this fanciful plan soon after announcing it and sold, or perhaps just withdrew their offer to purchase, the Hubbard lots and retreated to what they knew – building and renting fourplexes. Toronto in the late 1920s did have a smattering of affluent cosmopolitans who might have enjoyed American-style cocktails on a waterfront roof garden, but such people did not live in the Beaches, and a clear view of Lake Ontario was not going to draw them out.

The property was acquired, in 1929, by Arthur E. and Elizabeth J. Furniss, in partnership with their solicitor, Erell C. Ironside, who owned other lots in the new development as well as a summer house of his own further east along the lakefront. The Furnisses were well known to municipal authorities. It was they who had “outfoxed” the City (see Sight #5) and built on the beach – the Hubbard Court Apartments was their undertaking – and between them Mrs. Furniss and Mr. Ironside had owned some of the property on the south side of Hubbard that the City had expropriated in 1927 and, earlier this year, had agreed to compensate them $39,390 – a sum that probably helped finance the new endeavour.

By mid-1929 the Furnisses had completed their five buildings on the south side of Hubbard, facing the beach, lost their lots east of there to municipal expropriation, been compensated for that loss, and acquired the vacant lots on the north side.

The new owners wasted no time building what they called Hubbard Park Apartments on this newly acquired property. Who designed or built it, we do not know, but we know it had 27 not 86 suites, no roof garden, no swimming tank, no heated garages, and a foundation later revealed to be inadequate for the wet ground – the latter perhaps reflecting over-hasty construction. But it suited the neighbourhood, and its suites were immediately rented by the sort of people who lived in the homes around it: clerks, mid-level managers, and, especially, salesmen (11 of the 27 units in 1930).

The Furnisses held the property until 1940 when they sold it to a corporate entity named Hubbard Apts. Ltd.; it changed hands again a time or two over the decades and by the early 1970s was – rather curiously – owned by a couple who lived across the street on Hammersmith. By then the building was over forty years old, and like many aging buildings with non-resident owners and powerless tenants it had fallen into disrepair. No photographs or written descriptions of it have come to light, but directories reveal that several of its tenants were either retired or unemployed and that most of the those who were employed had low-wage jobs. There were exceptions, of course, but one gets the impression that it was a building for those who simply could not afford to live anywhere else.

Into all this, in the 1970s, came Toronto’s new reform council and the housing department it created to build and own affordable housing. One way the new department sought to accomplish its goal was by purchasing, with funds from Central Mortgage and Housing, older housing and making it available, at low rent, to eligible tenants. 42 Hubbard was among the first properties the City purchased, in October 1975, and it has been public housing ever since.

The City struggled to meet the cost of maintaining many of the properties it acquired under this program, and over the years some of the older buildings it purchased deteriorated, 42 Hubbard one of them. In 2009, after years of problems, the building was effectively condemned, and its tenants all relocated. But Toronto Community Housing, as its owner was then named, felt that both its location and its appearance made it worth retaining, so rather than sell it back into private hands – which it was doing with some of its other aging properties – it undertook a comprehensive reconstruction that involved, essentially, putting a new building inside the old brick shell. The fine, heritage-award-winning building we now see has no swimming tank or heated garages, but it does have a roof garden. It also, quite likely, has a long waiting list.

Davide Gianforcaro, Project Architect with Van Elslander and Associates, on a site visit.

From the dreams of the 1920s through the reality of the 1930s and 40s to the decline of the 1950s and 60s and the government interventions of the 1970s, Hubbard Park Apartments reflected the neighbourhood of which it was a part. And it still does. The Beaches of the twenty-first century is currently in the midst of what might be called the Age of Rebuilding, as so many of its old houses, if not demolished, have had their foundations strengthened and their interiors completely rebuilt, entailing heavy financial investment by owners and essentially creating functionally modern buildings that still look old – exactly the path that Hubbard Park Apartments and its owner, Toronto Community Housing, have followed.

SOURCES: (in addition to those cited under the images): CTA, Assessment Rolls, various years; Toronto City Directories, various years, accessed at website of TPL, digital city directories; CT Bylaw 11340, 26 Sept. 1927; Toronto Board of Control Report #1, CTCMs 1929, Appendix A, pp. 37-8; “Ten Unit Apartment for Scarboro’ Beach” and “Big Roof Garden a Feature of Scarboro’ Apartment,” The Globe, 2 July 1928, pp. 10-12; “City Non-profit Acquisition and Renovation Program”, Report #4 of Committee on Urban Renewal, Housing …, 3 Feb. 1975; CT Non-profit Housing Corporation, “Summary of Rental Projects,” 1976-1979; “A Homecoming for Dozens at 42 Hubbard Blvd.”, East York Mirror, 16 Jan 2012;personal correspondence with Terence Van Elslander, Van Elslander and Associates Architects; contemporary photographs by author.

Interesting that the first map in this Sight (Registered Plan #490, 26 Nov 1925 [Ontario Land Registry]) shows what looks to be a water feature in the upper right-hand corner. This is no surprise, given that the Glen Stewart creek abuts the north side of Queen Street at this point. The creek has gone underground south of Queen, but the evidence of the watercourse can be seen on the east side of Glen Manor Drive, where many of the houses are no longer particularly perpendicular, presumably because of the destabilizing effect of the groundwater.

It would be interesting to know how the City has dealt with all the springs, streams, freshets, etc. that flow through the Beaches. The City’s Engineering Department must have maps and plans that show all these underground conduits, since they are all still in active use, presumably.

Thanks for the site and the Sights!

LikeLike

Sure enough – those markings depict wetlands, the consequences of which, as you say, can be seen today along Glen Manor. Queen Street was filled quite early on, in the 1890s, to allow the streetcar to run through to the city boundary at Maclean, and the result was a large pond that is now Ivan Forrest Gardens. Details about landfills like this are not easy to find, but records do exist. Have a look at Sight #7 for a remarkable landfill story.

LikeLike

Thank you for this. I’ve suspected for some time that the Price Brothers never built the grand apartment building talked about in the 1928 article. Thank you for confirming it. On another note, the photo of Leslie, Joseph, and Earl Price is mislabelled in the original. Leslie is on the left, not the right. Earl is on the right.

LikeLike

Good to know. Thanks.

LikeLike